Why Edwin Meese the Third is Like William Jardine

As you may know, it is fairly easy to watch or listen to anything you want here--TV shows, documentaries, films, etc. Intellectual property rules are

mooshi like pork. Last night, I settled down fairly late, in my den and dressed only in my boxers, to watch Episode 2 (Opium), having not seen Episode 1 (Sugar), of a BBC series called

Addicted to Pleasure; it was supposedly view-able only in Scotland. The other two episodes deal with whisky and tobacco--two other scourges of the British Empire in which Scotsmen played a leading role.

In this segment on opium, though, Brian Cox does a brilliant job of jogging our memories about two-hundred years of history...except, as he notes, he is not jogging our memories at all, because, as in America, the Scottish textbooks are markedly devoid of mentioning the two major opium wars (First Opium War from 1839 to 1842 and Second Opium War from 1856 to 1860) or much at all about the trading of opium with China, which began in the 1630s. On the other hand, as well-dressed, Chinese-born

Professor Yangwen Chen from the University of Manchester proclaims into the camera with a righteously accusatory edge in her voice:

[In China] textbooks from elementary school to middle school to high school to university highlights [sic] the wrong-doings of the so-called imperialists. Students would be led to the site where the opium war took place. It has become part of what they call the patriotic education program to educate Chinese youth like me so that we remember what you have done to us.

In fact, the Battle of Peking in 1900 and the invasion of the Eight-power Allied Forces is also a small entry in most history texts, usually under the pseudonym "The Boxer Rebellion." The

British & World English Dictionary still defines

Boxer as, "a member of a fiercely nationalistic Chinese secret society that flourished in the 19th century. In 1899 the society led a Chinese uprising (the Boxer Rebellion) against Western domination that was eventually crushed by a combined European force, aided by Japan and the US."

Anyway, of the opium-focused episode that I watched,

BBC's short review states:

Scotland is plagued with over 50,000 drug addicts and one of the roots of this addiction is the opium poppy. In this second episode, actor Brian Cox travels to China to discover how the seeds of this modern-day addiction were planted during the height of Britain's trading empire. Since then opium has fuelled the world's largest drug-smuggling operation, earned vast fortunes, triggered war with China and inspired medical breakthroughs. Brian Cox reveals how Britain unleashed the most dangerous of addictions on the world, and how the consequences still haunt us today.

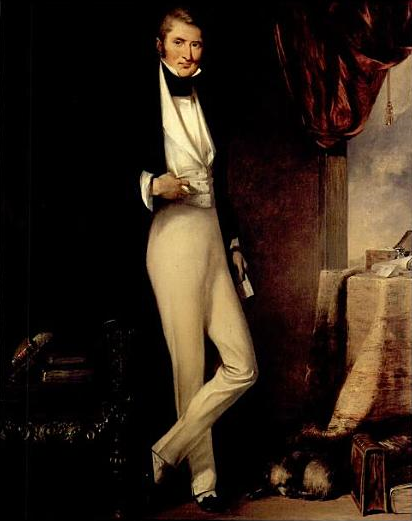

This tells you only a little bit, though. The illustrative tales that Mr. Cox brings to life are, as he notes with a nervous laugh, exceedingly cruel and pervasive. In the days of yore, missionaries brought "Jesus pills" of heroin and morphine to cure people of their addiction to opium, which was smoked, drunk, and otherwise imbibed until the invention of the hypodermic needle. More than 13 million Chinese were addicted to opium at one point. The Canton System gave rise to nine factories in Guangzhou (aka Canton) that were raided by an angry Qing emperor. Fighting broke out and the future barons and Members of Parliament William Jardine and James Matheson, two trading partners who controlled a major proportion of the opium trade, won their place in British history. The junior Matheson was sent slinking home by his business partner, Jardine, to convince Parliament to send ships.

|

| William Jardine |

Jardine, Matheson Co. (now Jardine Matheson Group) is still a going concern with a towering office complex in Hong Kong that employs more people in its conglomerate than any entity but the government. Its website innocuously states, "Since its foundation Jardines has been one of Asia's most dynamic trading companies, often having to reinvent itself in order to survive and prosper. Reflective of the times in which it traded, the Group has led the way in many businesses and has helped bring prosperity to the region."

They do not mention the word opium once in the

three segments of their company's timeline that stretch from 1830 to 1939. Still, there is little debate about what happened. I suppose certain past leaders of Iran could pretend that it never happened, much like The Holocaust, but historians mostly agree:

Jardine and Matheson led England to war. Actually, they marshaled the Royal Navy for a wholesale slaughter in Britain's most ignominious war.

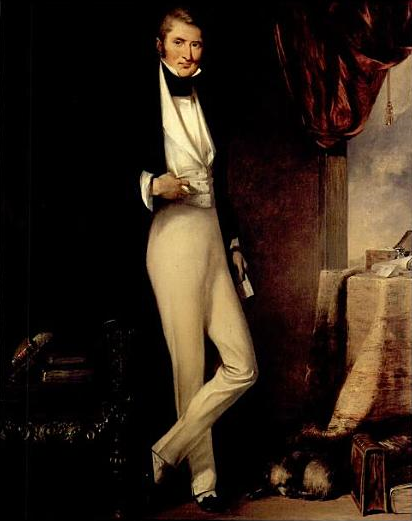

This is decidedly on point today, because when historians write the history of our times, they will need to tell the story of how

the government shutdown was orchestrated by angry billionaires. Edwin Meese III is one unpatriotic, despotic, sick old man. I remember him from 1986 when I did my very first research paper for Mr. Green on Meese's messy role in the Iran-Contra Affair. Meese resigned in the wake of the

Wedtech Scandal just a bit later. He is the William Jardine of today. Out of incredible self-interest, he is prodding our nation's "leadership" to do things that will be judged immoral and outrageous by future generations.